TLDR

As content becomes cheap and instructional delivery increasingly automated, the traditional value proposition of in-person undergraduate education must be redefined. This article introduces a 5-part framework: Formation, Community, Signal, Experience, and Alignment, to evaluate what remains defensible in a high-cost degree. It outlines practical implications for university leaders, EdTech companies, and investors, and makes the case that the future of higher education lies not in resisting change, but in delivering what technology cannot replicate: structure, standards, judgment, and trust.

A Silent Shift With No Clear Strategy

In many classrooms today, students submit assignments they’ve drafted with machine assistance, and receive feedback their professors generated the same way.

Faculty use AI tools to outline lectures, prepare reading summaries, and draft preliminary comments on student work. Students use AI tools to conduct research, organize ideas, develop responses, and receive feedback before anything is submitted. This dynamic now shapes how learning occurs inside the classroom and how performance is evaluated. In some classrooms, this happens openly. In others, it’s unspoken but understood.

Despite this shift, many colleges have not meaningfully changed how they define, price, or deliver the undergrad academic experience. Most continue to emphasize content access, course libraries, and branded instructional platforms. Education technology vendors still prioritize scale and integration over substance. Investors tend to reward automation models that promise cost reduction rather than improved outcomes.

Yet the core problem is not technical. It is strategic.

The tools have changed. The institutional operating models largely haven’t.

The market no longer values content in the same way, but higher education continues to treat it as the foundation of its product.

This raises a fundamental question:

If instructional content is widely accessible and rapidly produced, what remains defensible in the traditional, high-cost college experience?

Many institutional leaders know the answer to this intuitively.

But very few are intentionally building strategy, operations and communication around it. The result is a widening gap between what colleges quietly rely on to justify their value—and what they publicly emphasize, measure, or invest in.

The Erosion of Content as Value

For years, undergraduate instruction has been delivered in formats that were already beginning to lose relevance. Large lectures, generic assessments, and platform-based course delivery were common before the recent wave of new tools emerged. In many cases, these models were adopted for reasons of scale, not effectiveness.

Now, most core materials: lecture notes, explanations, readings, and study aids, can be replicated at little or no cost. In some areas, alternatives are clearer, faster, and easier to use than institutional systems.

Students are aware of this. So are faculty. So are many employers.

The real surprise is how little this awareness has changed the core undergraduate academic product.

This article is not implying that higher education no longer matters. It suggests that the academic model built around content delivery is no longer sufficient on its own.

The long-term value of an undergraduate education was never meant to rest solely on access to information. Its relevance depended on something more difficult to quantify: who students become, what they can do, and where the experience leads them.

The challenge now is to make that implicit value explicit, and to structure it in ways that justify continued investment.

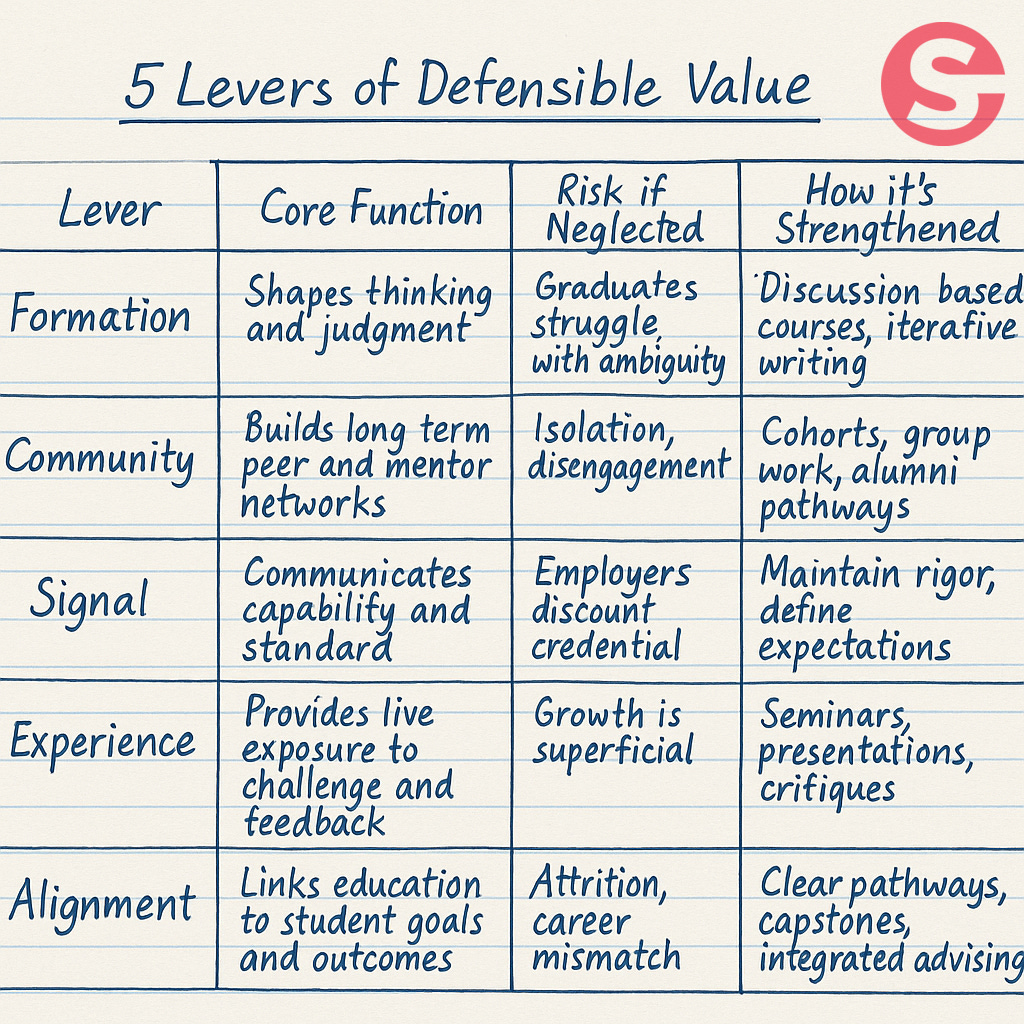

The 5 Levers of Defensible Value in Higher Education

The future of the ~$0.5 million in-person college experience depends on institutions delivering something else: something more lasting, more specific, and more difficult to reproduce outside a structured academic environment.

At Emerging Strategy we’ve developed a practical framework to evaluate and strengthen the parts of the in-person undergraduate experience that continue to carry long-term value.

These are not aspirational qualities. They are operational levers and each one reflects a function that universities perform when they are at their best—and each one, if neglected, becomes a source of risk.

You could think of these as the five non-exportable assets. They don’t travel well outside of strong programs, but they’re what still justify a premium.

In my work with education companies, institutional leaders, and investors, I focus on helping them evaluate and strengthen these five levers especially as their traditional models are under pressure. Whether the goal is repositioning a degree, refining a product, or making a program strategy defensible in the market, the work begins by clarifying what still drives trust, outcomes, and long-term value.

1. Formation

The structured development of thinking, communication, judgment, and maturity.

This includes written and verbal expression, ethical reasoning, and the ability to interpret information and act under uncertainty. It is reinforced through courses and learning models that involve discussion, iterative work, and real feedback. It is weakened when instruction is limited to recorded lectures, multiple-choice assessments, and pre-scripted feedback flows. If a student can earn an ‘A’ without ever being asked to revise, reflect, or explain their thinking aloud, the system is signaling the wrong thing. Fewer large lectures and more seminar-style learning.

A recent survey of HR leaders and early-career employees sponsored by Hult International Business School reveals a need for “undergraduate programs focused on developing ‘human’ skills, like communication and collaboration” to address the gap in workplace readiness.

Does the program ask students to think clearly, argue well, and explain their reasoning—in writing and in speech?

2. Community

The student-faculty relationships and peer networks that shape professional direction and personal growth.

This includes informal accountability, study partnerships, shared ambition, and support systems that extend into the early career years. These relationships form naturally in high-contact, in-person programs, and are reinforced through group work, cohort structures, mentoring, and shared experience. They are harder to build in asynchronous, transactional formats. Most institutions talk about belonging. Few effectively resource it.

According to Inside Higher Ed’s Student Voice Survey, “data indicates that students trust professors most…” Universities must lean into that more, and learn to tell that story better.

Can students name at least three relationships they formed during the program that meaningfully shaped their future path?

3. Signal

The institution’s role in certifying readiness to employers, graduate programs, and the public.

Degrees still carry weight in hiring and admissions decisions, but that weight now depends on what the credential signals about quality, standards, and selectivity. When institutions lower academic expectations or replace substantive evaluation with broad participation, they reduce the value of the signal. When they maintain rigor and communicate expectations clearly, the signal holds.

According to employer research commissioned by the Association of American Colleges and University (AAC&U), liberal arts skills are valued and sought out in the workplace but employers question student preparation.

Would a hiring manager or graduate admissions committee choose this program’s graduates over someone without a degree but similar technical skills? And if not, is the institution prepared to explain why they’re still worth the price?

Some lessons can be reviewed. Others have to be lived.

4. Experience

The environment in which students practice applying ideas under pressure, with consequences and context.

This includes live discussion, feedback that isn’t scripted, the discomfort of being challenged, and the process of revising one’s view based on evidence. It’s time the Oxford tutorial model became widely adopted in the U.S. It’s currently limited to a few selective liberal arts colleges such as Williams and Sarah Lawrence.

Throw late-night discussions, group debates, public presentations, and moments of uncertainty that require resilience. These elements cannot be simulated with slides and quizzes.

For all the talk of “real world readiness,” there is still no substitute for navigating a problem live, in a room, with peers who disagree.

Do students leave the program with a clear memory of having worked through difficult, unstructured problems that forced them to adjust?

5. Alignment

The degree to which a program’s structure, expectations, and outcomes reflect what students are actually trying to achieve, and what the job market, graduate programs, or other downstream paths require.

According to employer research commissioned by the AAC&U, "Completion of active and applied learning experiences gives job applicants a clear advantage." Meanwhile Strada Education Network’s student research indicates “Most students (70 percent) report that they were motivated to participate in an internship to gain experience in a specific career that they plan on pursuing as their chosen profession."

Alignment is not about merely offering job training. It’s about designing programs that make sense to students given their goals, and that hold up under scrutiny when evaluated by employers or selection committees. It includes:

- Ensuring program content matches the skills, knowledge, and decision-making frameworks students will need in their next step.

- Making course sequencing, degree requirements, and academic expectations transparent and coherent.

- Providing clear pathways to internships, research, or applied projects that connect learning to future use.

- Actively incorporating employer and alumni feedback into curriculum design and advising.

If the student sees no visible connection between their degree path and their intended path after graduation, they will rightly ask: What exactly am I doing?

If a student were asked six months after graduation whether the program prepared them well for their next step, would they say yes, without hesitation, and be able to explain why?

The most resilient institutions will be those that treat these five levers not as branding themes, but as operational priorities.

What This Means—for You

The 5 levers can be used to evaluate the actual value students derive from a program, and the institutional risk if that value is unclear or inconsistent.

Here’s how these levers translate into operational choices for the three major actors shaping the future of higher education: institutional leaders, edtech companies, and investors.

For Institutional Leaders

Many universities face declining enrollment, shifting student expectations, and growing skepticism from employers. The response has often been to increase marketing spend, add online programs, or cut instructional costs.

The better path is to reallocate attention and resources toward strengthening the elements of the in-person academic experience that still carry weight in the market.

Students still want to learn. They still want to grow. They still want to believe their investment of time and funds is worth the sticker price.

What to prioritize:

- Reinforce standards. The more rigor is reduced, the more the institution's signal loses credibility. If selectivity is declining, standards for output must be higher, not lower.

- Audit for alignment. Institutions should regularly evaluate whether their programs still match the goals of their students and the expectations of relevant employers. This cannot be outsourced to rankings or marketing language.

- Invest in community infrastructure. Advising, mentorship, student-led groups, capstones, and peer-driven experiences need physical and financial support. Without them, students lose access to long-term value.

- Redesign around feedback. Instructional quality improves when students are asked to revise, defend, and improve their work. This means fewer lectures and more writing, presentations, and discussion, especially in the second half of the degree. This isn’t about making college harder. It’s about making it matter.

- Streamline programs, not outcomes. Efficiency should come from removing duplicative content or outdated course requirements, not from reducing student-faculty interaction or delegating evaluation entirely to machines.

In my work with provosts, deans, and strategy teams we are navigating this exact set of choices: where to raise standards, how to reinvest in feedback and mentorship, and how to differentiate without adding complexity. The tradeoffs are real, but the institutions that work through them deliberately are the ones that maintain credibility and enrollment.

For EdTech Companies

Technology vendors that support higher education have been pulled in two directions. Some are asked to help institutions cut costs through automation. Others are expected to improve learning outcomes and retention. These are often in tension.

Firms with long-term relevance will be the ones that design around the five levers, not just platform features.

What to prioritize:

- Enhance faculty capacity. Tools that save faculty time should do so in a way that allows them to reinvest in mentorship, feedback, and presence—not exit from the learning process.

- Support unstructured learning. The strongest programs ask students to navigate ambiguity, revise their thinking, and engage with others. Platforms that support this kind of work will stand apart from systems designed around static modules.

- Enable better advising. Institutions need visibility into how well their programs are aligned with student goals and labor market shifts. Vendors who help surface these insights without bloating the tech stack will be well-positioned.

- Avoid replacing what matters. If the core product becomes a shortcut that reduces engagement rather than sharpening it, the institution’s long-term differentiation will suffer—and with it, the vendor’s position.

For Investors

There is no shortage of capital entering the education space. The risk is not in the availability of investment. It is in misreading what drives durable returns.

Content delivery alone is not a defensible moat. The same is increasingly true of automation-first models unless they are part of a broader institutional shift.

What to prioritize:

- Back infrastructure, not just instruction. The most resilient education companies will be those that help institutions deliver Formation, Community, Signal, Experience, and Alignment in ways that students, employers, and boards can recognize.

- Test for dependence vs. fit. If a product’s usage is driven primarily by budget cuts or labor substitution, it may face churn once conditions shift. Solutions that clearly improve student outcomes or faculty effectiveness are more stable over time.

- Distinguish scale from resilience. Fast user growth matters less if the product undermines long-term credibility. Tools that support what makes an institution distinctive are more likely to remain core to the academic model in the years ahead.

The market for undergraduate education is not disappearing. Institutions that clarify what they uniquely offer—and deliver it consistently—will remain essential. The same is true for the firms and capital partners that support them.

What has changed is that the burden of proof is now higher. In the past, students paid for access. Today, they pay for outcomes they can trust.

In our work with stakeholders across the education landscape, we often find that the challenge isn’t knowing what’s broken, it’s building alignment around what’s worth preserving, and designing around that with intention and discipline.

What Holds, and What Comes Next

The institutions that will endure are those that stop trying to defend instructional content as their core product. That phase is over. Content can now be generated, distributed, and accessed across multiple channels with little cost and minimal friction. This is not a future scenario. It is already the case in most classrooms, regardless of whether faculty or administration have formally acknowledged it.

The relevant question is no longer “How do we teach?” It is “What remains worth delivering in person, with care, at full cost?”

The answer lies in five areas:

- Students still want to be shaped by serious intellectual work.

- They still want to belong to something that outlasts the transcript.

- They still want credentials that carry real weight.

- They still want to be challenged, in real time, by people they respect.

- And they still want a clear link between the work they do and the life they want to build.

These are not sentimental ideals. They are practical, measurable, and achievable—but only if institutions choose to orient around them deliberately.

In the past, these outcomes were treated as the byproduct of enrollment. Now, they must be treated as the product itself.

Colleges that adjust their operating models accordingly will stabilize. Those that don’t will spend the next decade in a cycle of price discounting, retention decline, and reputational drift. The same is true for technology providers and capital partners. Success in this space will not come from doubling down on efficiency. It will come from helping institutions deliver what students, employers, and society continue to need—an environment where people learn to think, grow, and decide with clarity and accountability.

The strongest institutions will not be those that resist new tools. They will be those that integrate them without losing sight of what makes their work matter.

That is the future of the $80,000 classroom. Not as a delivery vehicle. But as a place where knowledge is tested, character is formed, and real preparation happens—under pressure, with support, and in full view of others.