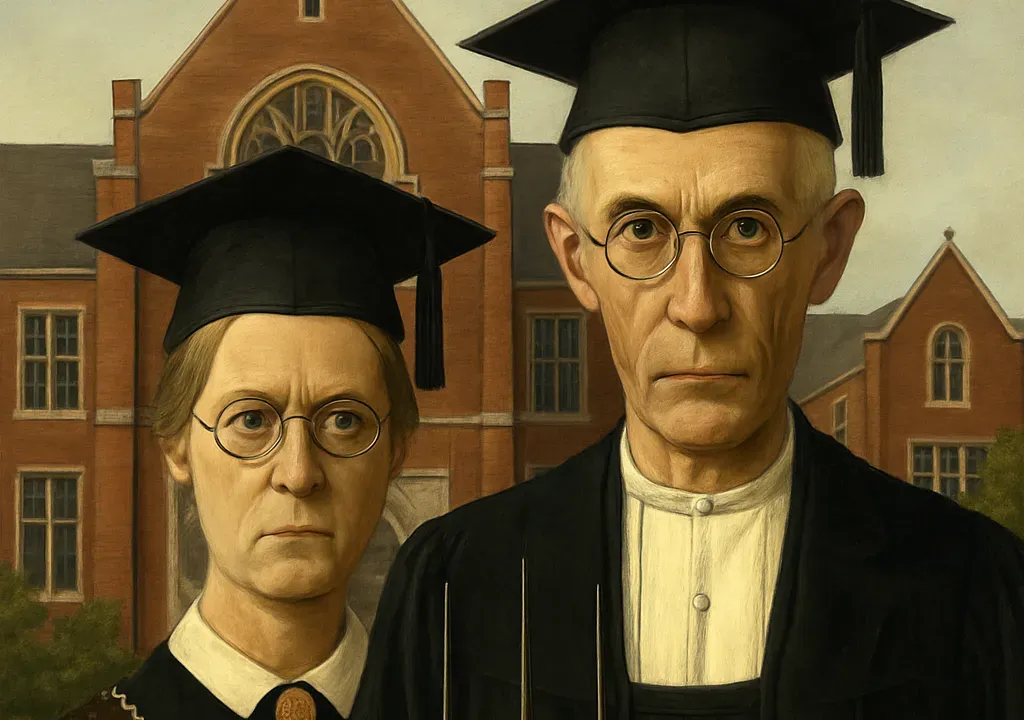

In Macomb, Illinois, a prairie town once anchored by Western Illinois University, the signs of unraveling are everywhere. Half-empty storefronts. Rising poverty despite an educated population. And a regional university that has lost more than half its students since 2006.

Macomb isn’t the exception. It’s America’s quietest economic crisis.

Across the country, small and mid-tier colleges, especially those in rural or post-industrial towns, are bleeding enrollment and drifting toward insolvency. When these institutions falter, their host communities don’t just lose students. They lose jobs, tax revenue, civic identity, and a shot at upward mobility.

Between 2016 and 2024, over 90 colleges closed or merged across 34 states. According to IMPLAN’s economic modeling, the average college closure results in the loss of 265 jobs and $14 million in local labor income. Multiply that by dozens of closures, and the damage to local economies becomes systemic. For towns that lack industry, this is the equivalent of a plant shutdown. Except instead of steel or cars, the factory was producing educated people.

And the shutdowns are accelerating. Thirteen institutions closed in 2024 alone.

Four Futures, One Choice

1. Macomb, Illinois – Western Illinois University

Enrollment halved. Budget slashed. Town in population decline. Cuts helped short-term, but deeper revitalization still elusive.

2. Presque Isle, Maine – UMPI

Remote campus redefined itself through adult-focused online degrees. “YourPace” program drove 74% enrollment growth. Small town, but national reach kept it viable.

3. Pennsylvania – PASSHE Integrated Universities

State system merged six regional campuses into two. Paired with tuition freeze and funding boost. Early signs of stability after steep decline.

4. Poultney, Vermont – Green Mountain College

Closed in 2019 after long enrollment slide. Nonprofit later repurposed campus, but economic recovery for town remains slow and uncertain.

The Demographic Cliff Is Now a Reality

American higher education was already facing a long-term squeeze pre-COVID. The number of college-age students, driven by post-2008 birth rate declines, has been dropping. Total college enrollment fell 15% between 2010 and 2021, per the National Center for Education Statistics. COVID simply broke the dam: undergraduate enrollment declined by 1.16 million students between spring 2020 and spring 2023.

This isn't just about young people. It’s about value. Families are rethinking whether a $30,000-per-year regional college with middling career outcomes is worth taking on debt for. At the same time, a tight labor market has pulled many would-be students directly into jobs. And even those still interested in college are now making ruthlessly pragmatic choices. They’re choosing institutions with strong brand equity, proven ROI, or flexible programs. The middle is getting squeezed.

International enrollment, once a pressure valve for declining domestic numbers, is also failing to save these institutions. Undergraduate international enrollment actually declined by 1.4% last year, with the number of Chinese students, historically a major revenue source, down another 4.2%. With policymakers in Washington DC broadcasting disdain for international students, it is unlikely that international enrollments and the dollars they bring will pick up in the near term.

Lacking global brand recognition or recruiting reach, these schools remain vulnerable especially as visa policy continues to shift. During the first Trump administration, tighter visa rules helped drive a 12% drop in international enrollment.

In short: the customer base is shrinking. And the ones shopping are more selective.

What Happens When the College Goes Quiet

In college towns, enrollment is an economic engine. Every student supports a constellation of jobs, businesses, and services: coffee shops, landlords, barbers, substitute teachers, local transit. When enrollment declines, the effects ripple far beyond campus gates.

Take Macomb again. Western Illinois University’s enrollment fell from nearly 10,000 in 2006 to just over 5,500 today. The university slashed its budget by over $25 million, cut academic programs, and laid off faculty and staff. Local businesses closed. Property values stagnated. The city’s population dropped by nearly 40% from its peak, and the poverty rate remains stubbornly high, even though a larger-than-average share of residents hold college degrees.

The losses compound: fewer students means fewer graduates staying in town, fewer renters, fewer bar tabs, fewer entrepreneurial sparks. Only 1 in 5 WIU grads from the class of 2009 were still working in the Macomb region nine years later. By contrast, urban universities like Wayne State in Detroit or the University of Houston often retain over 75% of their graduates locally.

Across the country, the same story repeats. Vermont’s Green Mountain College shut down in 2019, triggering layoffs and business closures in the town of Poultney (population: 3,300). Iowa Wesleyan closed in 2023 after 181 years. Many of these towns are now chasing modest redevelopment plans: co-working spaces, agritourism, historical preservation grants, to replace what was once their beating heart.

From 2022 to 2024, 27 U.S. colleges closed.

Some state governments are beginning to treat colleges not just as educational providers but as regional infrastructure. Others still treat them as liabilities to be triaged.

Consider Pennsylvania. The state’s public higher ed system (PASSHE) had seen a 30% enrollment decline since 2010. Instead of watching its regional campuses collapse one by one, the state approved a substantial increase in funding and facilitated the merger of six universities into two operating entities. Tuition was frozen for seven consecutive years, and the system began reporting modest enrollment gains again.

Vermont followed a similar path, merging three financially unstable colleges into a unified Vermont State University, backed by transitional state funding. Alabama even considered bailing out Birmingham-Southern College, a private liberal arts institution, on the grounds that its closure would devastate the surrounding community. The move was controversial, but the logic was clear: the costs of collapse may outweigh the costs of support.

Not every state sees it this way. Illinois, during a prolonged budget impasse, effectively starved its public universities.

Reimagining the Value Proposition

Many small-town colleges were built to serve a local population of recent high school graduates seeking a four-year degree and a middle-class life. That model worked, until enrollments dropped and the middle class stopped growing. Now, these institutions are being forced to ask harder, more strategic questions: not just how do we grow? But why do we exist at all?

Survival is no longer about broadening access to content or adding programs. It’s about offering something students and communities can’t easily find elsewhere, and doing so with clarity. As explored in a recent piece on the future of the undergraduate experience, the institutions that endure will be those that stop treating instructional content as their core product, and instead orient around outcomes that are harder to replicate: structured growth, meaningful relationships, discernible standards, and real-world alignment.

This shift is already underway—if unevenly.

Some schools are realigning their academic offerings around labor market demand. Programs in nursing, logistics, cybersecurity, and business analytics are replacing under-enrolled majors. Importantly, these are not just "career tracks" but opportunities to deliver on what students increasingly expect: programs that translate into forward motion.

Others are developing flexible formats: short-term certificates, hybrid courses, evening schedules—designed not for 18-year-olds but for the working adults in their own backyards.

Then there’s the more fundamental rethinking of mission: colleges acting as regional economic engines. This means not just educating students but co-creating solutions with employers, incubating local business activity, and anchoring civic development. The University of Nebraska partners with the state on agricultural robotics through the Heartland Cluster initiative. Others, like Albion College in Michigan, are securing public grants to renovate their downtowns, positioning the college not just as an educator but as a civic engine.

Delivering the core experience of formation, community, experience, and alignment matters, and this require operational choices, not just aspirational messaging. The most promising institutions are the ones that have begun treating those qualities as design problems. They’ve stopped waiting for traditional enrollment to rebound and started building relevance one partnership, one program, and one student outcome at a time.

In our work with institutional leaders and product teams, we help surface what students and stakeholders actually value and how those perceptions diverge from internal assumptions so strategy can be grounded in real insight not wishful thinking.

6 Proven Strategies to Reverse Decline

For colleges that act early and decisively, there are viable paths forward. The strategies that show the most promise are not grand transformations, but deliberate reorientations: toward new student segments, clearer value propositions, and tighter institutional focus. Here are six approaches that have generated meaningful results.

1. Adult Learners and Online Flexibility

The University of Maine at Presque Isle (UMPI) offers one of the clearest examples. Facing enrollment decline and geographic isolation, UMPI launched the “YourPace” program: an online, competency-based platform aimed at working adults. By untethering degrees from semesters and campuses, UMPI attracted students far beyond its region and grew enrollment by 74%.

2. Transfer Pipelines That Actually Work

Maine’s public university system created a seamless pathway from community colleges through its “Transfer ME” program, resulting in a 39% jump in transfer enrollment. These are students already sold on the idea of higher ed. They just need frictionless access and affordable options. Many institutions talk about “stackable credentials.” Fewer have aligned incentives and academic calendars to make the handoff smooth. Maine did.

3. Retention as a Revenue Strategy

In an environment where every new student is harder to acquire, the quietest source of enrollment stability is retention. Institutions are doubling down on success coaches, mental health resources, and predictive analytics to catch academic attrition early. This is customer retention dressed as student support. Retention doesn’t make headlines, but it prevents slow leaks that silently hollow out a class.

4. Academic Offerings Aligned with Demand

Curricular triage is difficult, but necessary. Some institutions have cut programs with persistently low enrollment and reinvested in areas with demonstrated demand. That doesn’t just mean tech or business. It can mean conservation, law enforcement or outdoor recreation management, if those fields match local assets and national interest. The strongest moves are those that align what we offer with who we serve and where we are.

5. Smarter Recruitment and Positioning

Gone are the days of waiting for high school visits and glossy brochures to do the work. Smaller colleges are expanding their geographic footprint by marketing more aggressively to out-of-state and international students, especially those seeking value, flexibility, or specific programs. CRM tools, digital advertising, and test-optional admissions have widened the funnel. But reach without clarity doesn’t convert, so institutions are sharpening their messages, not just amplifying them.

We’re working with institutions and edtech firms to deliver insights on the decision patterns behind enrollment behavior: what drives commitment, what causes drop-off, and where positioning breaks down by audience segment or delivery model.

6. Community Revitalization as Enrollment Strategy

Some colleges are addressing an often-overlooked barrier to enrollment and retention: the town itself. Albion College, for instance, collaborated with alumni investors and local government to transform its struggling downtown into a livable, walkable college town again. The rationale is strategic: students and parents don’t just choose an academic program. They choose an ecosystem. If the town is dying, so is yield.

The throughline in all these examples is operational clarity. None of these institutions tried to be everything to everyone. Instead, they matched their strategic decisions to the students and stakeholders who still had a reason to care.

Reinvention or Drift

Small-town colleges are no longer buffered by tradition or geography. The forces acting on them: demographic contraction, rising costs, changing student expectations—are structural, not cyclical. Waiting for things to return to “normal” is a bet most can’t afford to lose.

The strongest responses begin with a reframing of purpose: What do we uniquely deliver now that content is free, student trust is fragile, and the old assumptions no longer hold?

In our recent work with education institutions and investors, we’ve seen how early clarity on institutional posture, audience fit, and program-market alignment can determine whether an investment becomes a turnaround story or a slow-motion exit.

Whether it’s through new student segments, lifelong learning infrastructure, regional economic integration, or just tighter alignment between mission and execution, there IS an opportunity to not only survive but to become relevant again.

Some will do this. Others won’t. The dividing line is not resources. It’s posture.

Fix the purpose, flex the model, or drift toward irrelevance.

The real question for small-town colleges and their communities isn’t “can we survive?” It’s “are we still willing to matter?”